In the jianghu, you break the law to make it your own.

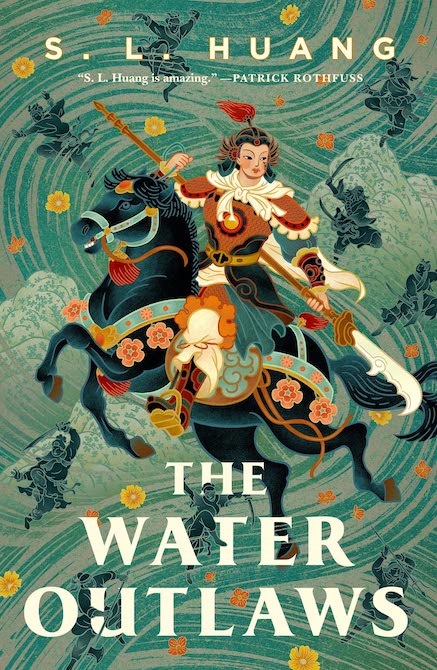

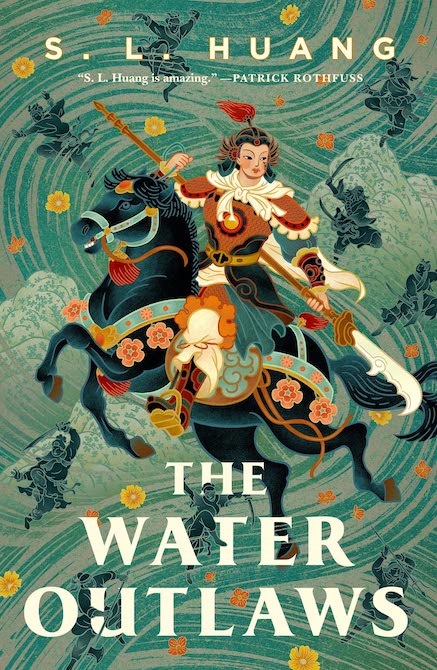

We’re thrilled to share an extended excerpt from The Water Outlaws by S.L. Huang, out from Tordotcom Publishing on August 22.

[CW: attempted sexual assault.]

Lin Chong is an expert arms instructor, training the Emperor’s soldiers in sword and truncheon, battle axe and spear, lance and crossbow. Unlike bolder friends who flirt with challenging the unequal hierarchies and values of Imperial society, she believes in keeping her head down and doing her job.

Until a powerful man with a vendetta rips that carefully-built life away.

Disgraced, tattooed as a criminal, and on the run from an Imperial Marshall who will stop at nothing to see her dead, Lin Chong is recruited by the Bandits of Liangshan. Mountain outlaws on the margins of society, the Liangshan Bandits proclaim a belief in justice—for women, for the downtrodden, for progressive thinkers a corrupt Empire would imprison or destroy. They’re also murderers, thieves, smugglers, and cutthroats.

Apart, they love like demons and fight like tigers. Together, they could bring down an empire.

Chapter 1

Every morning just after dawn, Lin Chong taught a fight class for women.

The class was always well attended, and Lin Chong welcomed any from the lowest beggar to the highest socialite. Women choosing to apply themselves so seriously to the arts of war and weaponry might have been seen as unusual, even in the highly modern Empire of Song, but Lin Chong was so well established in the prefecture, and so well respected, that men rationalized the participation of their wives and daughters. It will help her excise any womanly hysteria, they would think, or She will be able to improve her grace and refinement. Besides, they trusted Lin Chong not to be too rough, or to act inappropriately. She was, after all, a master arms instructor for the Imperial Guard, and besides which was also a woman herself.

If the men had ever come to watch their wives and daughters at work, they may have revised their concerns about the roughness.

Today, after a meditation and warmup, Lin Chong had divided her attendees into pairs to practice a new combination of techniques. A block and throw—very useful, especially for a weaker opponent against a stronger attacker. Lin Chong paced between the pairs, watching, adjusting, correcting. Occasionally she even added a short word of praise, which inevitably made its recipient glow.

Buy the Book

The Water Outlaws

In the front of the group, Lu Junyi swept her opponent to the ground and gave Lin Chong a devilish grin. Tall, slender, and with a face an artist would invent, Lu Junyi had the same self-possession here, shining with sweat, as she would overseeing one of her intellectual salons. She kept Lin Chong’s eye and made a motion across the courtyard, as if to ask about the woman she had brought with her today.

Lin Chong only nodded her back to work. They might be old friends, training under Zhou Tong together back when they were both barely nineteen, but that was no excuse for inattention during class.

Lu Junyi gave a good-natured sigh and reached out a hand to help her opponent up.

Lin Chong did need to see how the new participant was faring, however. She’d heard some grunting and swearing from that corner that did not presage well. She turned and circled in that direction.

When Lu Junyi had introduced Lu Da before the class began, Lin Chong had not exactly been surprised—despite her social status, Lu Junyi somehow managed to meet a wide diversity of people. And Lu Da was an eclectic patchwork of the human condition all by herself. The sides of her head were shaved in the tradition of a monk of the Fa, but the ink characters of a criminal tattoo marched down her cheek, and her mannerisms were as far from a monk as could be imagined. When Lu Junyi had introduced her, Lu Da had spit on the flagstone ground and then nearly shouted her salute, smacking her hands together so hard the respectful gesture might as well have been crushing a melon. She was likely strong enough to crush melons, too— she towered over the other students, and her girth was were easily twice Lin Chong and Lu Junyi put together. But she’d seemed an eager enough student, bounding over to leave her heavy two-handed sword and even heavier metal staff at the side of the practice yard at Lin Chong’s direction.

When Lin Chong stepped back over to her, however, it was to find that Lu Da and her opponent had somehow devolved into a wrestling match.

Lu Da had her partner in a bear hug and was squeezing her so hard her feet had come off the ground. But the other woman had been training with Lin Chong for many months, and she managed to twist and break the hold. She dropped back to her feet and spun lightning fast.

“Why, you donkey!” Lu Da bellowed, and swung a massive fist, which her partner dodged.

Lu Da let out a roar that seemed to call earth and wind to her command. She thrust out a palm, striking the empty space between them, and from a full pace away blasted her opponent back. The woman flew into the air only to land on her back and roll until she hit one of the neighboring buildings.

“Stop,” Lin Chong said.

She didn’t speak loudly, but she never had to. The entire class halted and turned to attention from where they were. Several of them had already been distracted into watching Lu Da, their faces dazed and fascinated.

“Attention,” Lin Chong said.

The class drew their feet together and stood straight, hands behind their backs. Lu Da looked around and then clumsily imitated them.

“You are uninjured?” Lin Chong asked the woman who had hit the ground.

She scrambled back to her feet. “Yes, Master Instructor.”

Lin Chong turned to address Lu Da. “You have a god’s tooth.”

Lu Da had the grace to flush red across her broad face. “I do, Master Instructor.”

“Show me.”

Lu Da pawed at her loose collar. Beneath her tunic, a magnificent garden of tattooed ink peered out, far more wild and fantastical than the impersonal criminal brand on her face. She grabbed at a long leather cord around her neck and drew it forth to reveal a shining shard of stone or porcelain.

The piece hung from the leather, smooth with age and deceptively inert, and drawing every eye in the class.

Lin Chong raised her voice to the class again. “Who here considers themselves a philosopher?”

About a third of the class lifted a hand.

Lin Chong shook her head slightly. “I don’t mean you tell your children to follow the tenets of Benevolence, or you make sacrifices to the gods for favors of luck or wealth. Who here dedicates themselves to the practice of one or more religions?”

Most of the hands went down.

Lin Chong nodded to a young woman in the front, a newer student she didn’t know well yet. “Yes. Which do you practice?”

“I follow both Benevolence and the Fa, Master Instructor.”

Perfect. “And what do your religions teach you about the gods?”

She looked confused. “They don’t, Master Instructor.”

“Quite correct.” Lin Chong raised her voice, making sure the whole courtyard could hear. “The gods are irrelevant to the teachings of the Benevolent Order. The Fa teaches that gods differ from us only in an advancement of immortality and its power, and that all were once human—we could become the same by studying enough to attain enlightenment, and in fact, the early stages of enlightenment are what the Fa believe grant the abilities we know as ‘scholar’s skills.’ The Followers of the Fa aspire to move past mere scholar’s skills and attain that godhood, but otherwise do not look to the gods for help.”

She’d been pacing the front of the yard as she talked, and slowly came back around to face Lu Da.

“Student Lu. You are a monk of the Fa.”

“I was,” Lu Da corrected genially. “They kicked me out.”

Lin Chong could feel her eyebrows rise. “You were expelled from the monastery? Why?”

“I missed curfew,” Lu Da answered.

“I see.”

“A hundred and seventy-three times.”

“That would—” started Lin Chong delicately.

“Because I was drunk!”

Lin Chong waited a moment to make sure nothing more was forthcoming. Then she said, “You still know the teachings, however.”

“Sure, whichever stuck in my head. They do leak out my ear-holes.”

“Then tell us, Student Lu. What is a god’s tooth?”

Lu Da flushed a bit redder. “It’s like you said. You know. They told me not to use it, because, well, it’s the power the gods left behind, in artifacts and the like. Sort of cracks in the world, right? Wherever the gods went long ago, and the demons too, god’s teeth are what let that bust through a bit. But the monks said it doesn’t help me reach enlightenment, so I should put it away and never touch it. ‘God teeth never make a god,’ as the saying is.” She shrugged her massive shoulders sheepishly. “But they also always wanted me to be a better fighter, and my tooth makes me a better fighter!”

“The martial arts were to be your path to enlightenment?”

Again the sheepish shrug. “I’m good at them. Master Instructor.”

“Ah, but it is not raw power at your art that brings enlightenment, according to the Fa. You attain that only through the journey.”

“Right,” Lu Da said, sounding uncertain.

“Let me put it another way,” Lin Chong said. “After deep study, monastery training is known to grant scholar’s skills in your art, yes? If you studied hard enough, and long enough, you would learn to bend a fight to your will in ways even someone such as I—who has made a study of decades, of all five forms and across all the eighteen weapons—even someone such as I could never hope to best you. Do you think your god’s tooth does the same?”

“Well, yeah. That’s what god’s teeth are, right? Sort of a shortcut.”

It was what most people thought.

Monastery training was a route of great dedication and sacrifice that not many pursued, despite any potential reward. Many dreamed of leaping a building, of living for two hundred years, of having dream encounters with queenly demons—or any other number of storied scholar’s skills some monks and priests were said to develop depending on their study. If they stayed the path. If they excelled to the rights of legend. But the necessary years of strictness, of internal and external training, of mental and physical discipline…

A god’s tooth bestowed that power without strings. Without sacrifice.

Supposedly.

Lin Chong had already caught half her class casting glances of grudging envy at Lu Da. The Empire and the aristocracy had done everything they could for generations to push a social attitude of scoffing at god’s teeth, labeling them trinkets and fragments of a bygone age, ones outclassed by modern technology. But Lin Chong strongly suspected those most vocal in their dismissal were the ones who secretly coveted what they did not possess.

Certainly everyone here in her class was shaded in jealousy.

God’s teeth were power. They made things easy.

They were also rare enough that she might never see one in her class again. Lin Chong decided a demonstration was in order.

She faced the class.

“I am not religious.” She might remind herself of the tenets of Benevolence in daily life, as did most people, but she was no philosopher. More importantly, she was no monk. “I am not religious, and as I have said, I would never claim to be able to best the scholar’s skills of a monastery-trained monk. Student Lu. That is your staff, correct?”

She gestured to the heavy metal bar Lu Da had set aside before class. Easily taller than Lu Da, it looked to weigh at least sixty jin.

“Yes, Master Instructor!” Lu Da said proudly.

“It is your weapon of choice?”

“It is!”

“Then take it up, and face me with your god’s tooth.”

Lu Da stared in confusion. The rest of the class shuffled in their places, a few murmurs going up even among the well-disciplined students.

“But I’ll kill you,” Lu Da blurted.

“I admire your confidence,” Lin Chong said dryly.

“I wouldn’t try to kill you, I just mean I could hurt you bad…” Lu Da glanced around at the rest of the students, clearly trying to check whether she was speaking as honorably as she thought she was. After all, it wasn’t right to smash in the head of your teacher, was it?

“Take up your staff,” Lin Chong instructed. “Unless you are too afraid to face me.”

“I’m not afraid!” Lu Da shot back. She tucked her god’s tooth back under her tunic with her forest of inked flowers, then shuffled over to pick up the staff. She lifted it as if it weighed no more than a toothpick and whirled it above her head, in one hand and then the other.

“Clear an area,” Lin Chong said, and the other students hurried to gather up their reed mats and line the sides of the courtyard, whispering in anticipation.

Lin Chong took a moment to unwrap her heavy coat and lay it carefully to the side, along with the sword she’d untied and set apart before class. The robes underneath she tucked up in her belt, out of the way. Then she stepped to the middle of the courtyard, hands clasped behind her back, the hemp of her shoes quiet and sure against the flagstones.

“But Master Instructor! You won’t use any weapon?” Lu Da cried.

“I have weapons in my hands and feet,” Lin Chong answered. “I have weapons in my years, and in my training.”

Lu Da ambled in to face her, doubts scrawled transparently across her face. “This doesn’t seem all right. I don’t want to injure you.”

“You presume a lot, Student Lu,” Lin Chong answered. “I instruct you to wield the full power of your god’s tooth, and I shall wield my training, and we shall see if the monks of the Fa lied to you or not.”

Lu Da spun her massive staff between her massive hands. “As you wish, Master Instructor. I guess.”

“Begin.”

Lu Da’s face drew together in focus. She sidestepped, her staff at a slow spin, matching the same careful distance from Lin Chong.

Lin Chong stepped to pace her, evenly, calmly. Her hands stayed clasped behind her back. She breathed deep, inhaling the movement, the connections, the intricately fitted puzzle pieces of the universe.

The meditative state was as familiar as the moves of her muscles through forms, or the feel of a sword hilt or axe or halberd settling its weight against her hand. Familiar as worn cloth, calming as a childhood home. Like reposing to drink with old friends.

Lu Da reared back, and the movement rippled all through Lin Chong’s senses. Leaning to the side was an easy dance move, as if Lu Da had asked a question and Lin Chong answered without thought.

The heavy metal staff whistled through the air. A tentative strike, without Lu Da’s full weight behind it. Lin Chong could see the other woman’s balance, the way the weight was in her arms instead of backed by the vigor of her body.

“You hold back,” Lin Chong said.

Lu Da grunted and swung again. And again.

Lin Chong dodged once, twice, a third time. Always the smallest movement, always that fluid answer to Lu Da’s question. Before long Lu Da had forgotten her trepidation and was bringing the staff down with all her might, blows that would have surely crushed Lin Chong’s skull, had they landed.

“Your strength cannot bring you victory,” Lin Chong said calmly, slipping to avoid a downward swing, then twisting to let a thrust by.

Lu Da overbalanced, her face going red with exertion all the way up the sides of her shaved head to her bobbing topknot.

Lin Chong saw the moment Lu Da’s decision firmed, the instant her mind reached for the god’s tooth. Her posture rolled in on itself, her muscles tensing, her eyes squinting at the corners. She shouted her intention to Lin Chong as surely as if she’d proclaimed it from her lips.

Lin Chong felt the god’s tooth open.

Even the most minor god’s tooth tapped into something primal. Untamed. The deep caverns of a secret essence, the bright joy of an unbridled desire. A lack of inhibition that was difficult for even a studied practitioner to harness and guide.

Lu Da’s grasp on the power was tenuous at best. A whip streaking out that might snap against the intended target, or might smack a bystander—or might come rushing back to bloody the cheek of the one who wielded it.

She flung that power at Lin Chong.

It had been some time since Lin Chong had handled the power of the gods in a fight. But she remembered. She leapt, catching the edge of the wave and using it to climb an invisible staircase, foot to foot middair above Lu Da’s attempt. Then she landed lightly back on the flagstones, on the soles of her hempen shoes.

All with her hands still behind her back.

Lu Da stared in disbelief. Then she let loose.

The depth of the god’s tooth sucked free, thrashing against reality. Lin Chong lightly jumped one tendril of it, then let another wrap her leg just enough to snap it back with a kick of her foot. Lu Da roared, trying to wrest the power and aim it, but unsuccessfully. One curl of it slashed high on the next building, splintering a wooden screen over some of the windows. Another hit lower on the wall, causing some of the watching students to duck and cry out.

Lu Da was struggling to imbue the strength into her staff and ride it into a quick and crushing blow, but she was battling it as much as she was controlling it. As if she were attempting to raise a tiger by the nape of its neck and hurl its snarling and lashing claws in Lin Chong’s direction.

Lin Chong decided the demonstration had gone far enough. She leapt again, this time inward, toward Lu Da. One foot dancing against the groping power of the god’s tooth before it vanished in retreat or snatched her down; then the other diving closer. Lin Chong twisted like a snake to avoid the flailing of Lu Da’s heavy staff, her spine curving and arching around it. Just when she reached Lu Da’s side—a little way past—she dropped.

The sole of her foot arrowed down in the flesh behind Lu Da’s knee.

Lu Da squawked in surprise. Her knee came down hard on the stone, and she fell forward all at once, like a mountain that had been axed at its base. Her metal staff clanged against the flagstones.

Lin Chong landed lightly on her other foot. Around her, the power of the god’s tooth petered out. Like the last flickers of a dying flame, its effects fluttered out of the world, sucked back to the artifact that had granted them entrance.

Lin Chong’s students straightened cautiously, stunned and silent.

“Student Lu,” Lin Chong said.

Lu Da groaned a bit and rolled over. “You have beaten me, Master Instructor!” she roared dramatically from the ground. “I, the fearsome Flower Monk! I am yours to destroy!”

She flung her arms out to either side.

Lin Chong tried not to show reactions in front of her students, but it was so very difficult sometimes.

“Rise, Student Lu,” she said. “You are uninjured?”

She was almost certain so. She’d been very gentle.

“My pride, Master Instructor,” Lu Da said grievously, trying to scramble up. “The pride of the Flower Monk. Crushed under your feet.”

Lin Chong took her hands from behind her back and raised them in front of her. “I did not even use every weapon in my arsenal. You are many times stronger than I, and you wield a god’s tooth. Why did you fail to best me? What have you learned?”

“That you are very fearsome, Master Instructor!”

Lin Chong permitted herself a small smile. “Other than that.”

Lu Da’s forehead knitted up. “You… you train without the support of a god’s tooth, as the monks told me to. And that’s your weapon. One that can whale the piss out of me.”

“Eloquently put,” Lin Chong said. “If I had consistently leaned on a god’s tooth, I would have limited my skill either with or without it. God’s teeth may be power, but they are an artificial power—one you must still put in the years of work and training to control. They are no true shortcut. They are not the same as scholar’s skills grown from self-discipline and rigor. And just as your god’s tooth would have stymied you in your path to enlightenment with the Fa, Student Lu, it will stymie your training in the martial arts outside the monastery. You must have the finest control over yourself before you wield a power beyond yourself.”

Lu Da did not look entirely happy about that, her mouth turned down in an extravagant sulk. “And how long did it take you, Master Instructor?” she asked after a moment.

“More than four decades,” Lin Chong answered. “I have practiced my training for many watches of every day since I was a small child.”

“I’d rather drink wine,” Lu Da said. She scooped up her staff and shook herself out. “Four decades, aiya! I haven’t even lived three…”

Lin Chong turned slightly to face her class. “If you take one lesson from today,” she said, “let it be this. If you continue to train, with hard work and no shortcuts—no matter what beginnings you enter from—the control you have over yourself will equip you, unmatched, in any situation you encounter. Dismissed.”

Calls of “Yes, Master Instructor” and “Thank you, Master Instructor” floated up as the students bowed in her direction and began a disorganized exodus back toward the gates to the outer city. The murmurs swelled as they clustered together to gather their things, untucking gowns and robes and untying headwraps. Furtive, awed glances found Lin Chong where she still stood in the center of the courtyard.

“You kicked me into the ground today, Master Instructor,” Lu Da said jovially. “I did not enjoy it! But I’ll think about what you said. I still think I might like the shortcut.”

She saluted with a bow and ambled away across the flagstones, rubbing her various bruises.

“A fascinating person, isn’t she?” Lu Junyi had come up next to Lin Chong.

“Fascinating. Where did you meet her? Not at one of your salons, I would wager.”

“She was shouting on the street. Challenging some ruffians who would have abused a beggar girl. I helped defuse the situation and then bought Lu Da a bowl of wine—several bowls, strictly speaking. I told her about your fight class, and she insisted on coming to meet you. I think she is quite taken with you.”

“I don’t have high hopes she will have the discipline of continued study,” Lin Chong said, with a small sigh, “but if she does, she is welcome here.”

“She may surprise you. It would be good for her… She got that brand on her face for killing a man. Though for a reason you might be able to find approval for.”

“A civilian?” Lin Chong asked. As far as she was concerned, war was the only defensible context for killing another. “You may overestimate me. I could never excuse that.”

“Even a butcher who extorted and forced one of his concubines, only to throw her out on the street and insist she owed a debt to him? I hear tell he was a butcher in more ways than one. Nobody would miss a man like that.”

“Then the law should address it.”

Lu Junyi huffed out a breath. “I always forget how much more conservative you are than I. We women will have to take our power someday.” She reached up to unwrap her hair, untucking her robes and shaking them out. A brief drumbeat reverberated across the courtyard, from Bianliang’s towers where men struck out the watches of the day. “Aiya! Class ran long; I’m late. I have a meeting with Marshal Gao Qiu this morning, about my printing press. May I use your barracks to straighten myself?”

Lin Chong laughed lightly. Only Lu Junyi would play so fast and loose with her presentation before a grand marshal. “Of course. Come.”

“Good, and we can continue this conversation. I am not letting you out of the cause so easily.”

Lin Chong grunted. She did not share Lu Junyi’s passion for pushing the boundaries of society. Women in the Empire of Song today had more advantage than at any other time in history—Lin Chong herself was proof of that, advancing to a scholar-official position directly under Grand Marshal Gao Qiu. She had the respect of the people—of any gender—and even without the aid and status of a husband she had managed to arrange creditable stations and marriages for both her grown children, which she considered proof of her accomplishments.

Pushing harder would only lead to those opportunities being destroyed. Lin Chong could never countenance it.

Lu Junyi’s idealized visions betrayed her far more elevated place in society. Lin Chong might have an examination title, but Lu Junyi had been born to wealth and clan advantage. Without the gradual allowance for those of the female sex to burst from some measure of their historical strictures, Lu Junyi may not have owned her newly modern printing press, but she would have remained a charming socialite. Likely still high status, holding her salons, wealth and family name insulating her into being forgiven for the eccentricities of progressivism.

She could not understand. Small bites must be taken carefully, lest the whole meal be snatched away.

Lin Chong had much more to lose.

“You are the type of story men nod at as a successful example of the woman’s cause,” Lu Junyi pointed out, as they gathered their things and crossed the courtyard together. “But I do not think we can stop in the place where we still garner praise. I would like to see us have a trifle less approbation from men and a trifle more fear.”

“Violence is not the way.” Lin Chong thought of Lu Da, and her mouth folded into a frown. Violence was never the way. Anyone skilled enough in the fighting arts to be a master arms instructor knew that to her bones.

“Oh, not violence,” Lu Junyi said. “Not in the general sense. I only mean that as yet, our advancement has not come at the expense of men. But it shall. It must. There is not sufficient room for us otherwise. Our true success will mean some of them lose power… and that will not come without anger and fear.”

“Then we should slow its progress. A tidal wave spread over many generations becomes a gentle flow, and either one gets to the end.”

“A flow! You mean a trickle.”

“Even a trickle can wash away a mountain eventually.”

They continued the mostly friendly argument out of the courtyard and onto a stone-paved street toward Lin Chong’s rooms, which were adjoined to the barracks of the Imperial Guard. Bianliang’s inner city towered up around them, multistoried pagodas of brick and wood climbing up among the less-grand houses and offices. The inner city of the capital was the seat of government and Empire, and was several li across and as large as a small city itself—even as it lay nestled within the teeming population of the rest of Bianliang.

This was the inner city’s southern district, where the bureaucrats and soldiers of the central government lived and worked. A few people passed on the street, but not nearly as many as the bustle visible every time they came into view of one of the swooping, crimson-painted gates that led to the outer city. In the outer city streets, people and carts and carriages packed against donkeys and goats and hogs being driven to market, all hurrying and running and shouting in a steady stream.

Lin Chong’s rooms were airy and pleasant, if not expansive, with carved beams climbing the walls and windows whose shutters opened onto a garden. Lu Junyi took up a comb from the side table and settled on a stool, unwinding her hair to shake it out and begin brushing it smooth.

“Do you have any powder?” she asked. “I should not have come at all this morning, but I do hate to miss one of your classes. You should have a much higher position than master arms instructor.”

“I am perfectly satisfied with—”

“Oh, come now, we are alone here! You know what Marshal Gao Qiu is. He is a wet stocking. A trick of braggery and playing football with the Emperor. He toys with the city as if it is his playset—”

“Quiet!” Lin Chong hissed, glancing around. But they were alone in the small rooms. Outside the open windows, trees rustled over an empty garden.

“Ah, you know what I would say anyway,” Lu Junyi said, unperturbed. She began winding her hair up and fastening it with combs and clasps. “Gao Qiu is seeing me today about printing paper banknotes, if you would believe it. He read my circular on the subject. But do I expect him to understand or listen to my recommendations? No, I do not.”

Paper money. Lin Chong knew Lu Junyi’s arguments, but the idea did not sit well with her. Strings of coin and taels of gold and silver were heavy in your hand, worth something when weighed. What was paper worth? Burned in a fire, it would become nothing at all.

Lin Chong set her powder case down in front of her friend with a click against the polished table. “I will leave the intellectual arguments to you. I am content to remain in my post until I die. Marshal Gao has been nothing but fair.”

“To you,” Lu Junyi murmured, but she did Lin Chong the favor of not continuing, focused on fixing her face instead. Lin Chong knew what would have followed anyway: an accounting of all the plum positions Gao Qiu had granted to friends, all the political enemies he’d had jailed or sent to work camps, the favors he gobbled from the Emperor or the taxes he spent on lavishness for himself and his cronies.

Lin Chong could be aware of all this, and not condone it, while still seeing the wider context. Gao Qiu was her direct superior and had great political influence—and that would not be changed. His dealings with Lin Chong had been lazy but not malicious; he was worse than many men but also better than some. She could keep working for him, and would, and keep her opinions on his greater conduct to herself.

She kept her mouth tightly closed against the other whispers of Gao Qiu’s conduct, the ones that might anger Lu Junyi to the point of torching the entire inner city.

Lu Junyi finished retying her blouse, smoothed her skirts, and layered her long silk scarf into place across her shoulders. For a woman who had just spent the first watch of the day sweating in a courtyard, she had somehow assumed a refinement to her countenance that other society women lacked even after meticulous plucking and painting.

Lin Chong was old enough now not to envy it, and her position afforded her the ability to stay in her staid and functional robes, with no facepaint and her hair pulled back in a simple queue. It was a perk of her title she would be forever grateful for.

“I think I shall be just on time,” Lu Junyi said. “Now, will you point me toward White Tiger Hall? I am not familiar with that building.”

“White Tiger Hall? Marshal Gao is meeting you at White Tiger Hall?”

“Yes. What’s the matter?”

Lin Chong frowned, foreboding stealing over her. White Tiger Hall…

The inner city—the Imperial City—had three districts. Commoners could enter from the sprawling outer city only into the southern one, where they were now—the district that housed the grinding bureaucracy of the city government as well as the garrisons of the Imperial Guard. Gao Qiu’s yamen, with his rooms and offices, was here as well, and Lin Chong had never been called any other place for a meeting with him. Beyond the southern district, the central district existed for the Emperor to descend and meet with officials of far higher rank than Lin Chong. She’d only entered its gates a handful of times.

The central district was exceeded only by the north, which housed the Imperial Palace itself.

White Tiger Hall was in the central district.

It was where councils of war were decided on. Not the milieu for a simple discussion of economic policy in which the marshal was no doubt humoring his supplicant.

Gao Qiu has been nothing but fair… to you, Lu Junyi had said.

Lin Chong thought again of those other rumors. The ones she had been scrupulous about ignoring, never repeating, burying down in her consciousness with only a thread of wariness to protect herself, a thread that had, in her case, never been needed.

But Lu Junyi was a beautiful woman. A beautiful, unmarried, wealthy woman. Not as young as others, but it could not have been told from her energetic, unlined face. Unlike Lin Chong.

White Tiger Hall. Despite her defense of the marshal, apprehension gripped Lin Chong.

She did not share Lu Junyi’s passion for challenging the Empire or society. But protecting a friend…

That mattered to her very much indeed.

Lu Junyi caught her sleeve. “Sister Lin. What disturbs you?”

Lin Chong did not know how she could answer. All she knew was the way the uneasiness simmered in the pit of her stomach. “Would you mind if I accompanied you to this meeting?” she asked.

Lu Junyi’s eyes narrowed shrewdly. Then she said, “I would be honored. Please, lead the way.”

Chapter 2

Lin Chong led Lu Junyi deeper into the Imperial City, all the way northward until they climbed wide stone steps to another set of guarded, elaborately carved gates. Dragons and phoenixes were caught mid-furl among lofty clouds in the woodwork, overlooking any who would pass.

Lin Chong found herself thinking of the gods again, gone from this world so many centuries. Rumor held that dragons, too, had faded from the earth at about the same time. To the same place? For the same reason? Perhaps it was their power and not that of the gods that remained connected somehow, locked in the fragmented god’s teeth.

Unlike the gates to the outer city, which remained fully open as a matter of course, these gates were shut fast, with guards standing at attention on both sides. But many in the Imperial Guard knew Lin Chong by sight.

“Nuo!” cried the guards on either side, clasping their hands in salute.

“We enter by order of Marshal Gao Qiu,” Lin Chong announced, and the guards saluted again and unbarred the heavy crimson gates to haul them open for the two women.

If the southern district had been sparse, the central district was a city of ghosts. Aside from the odd guard or servant crossing at a distance, nobody passed on the streets or between buildings. The architecture here was more colorful, more elaborate, more storied. Swooping, brightly tiled roofs pierced the sky. Columns and brackets blossomed into their eaves with intricate carvings.

Lu Junyi looked around curiously.

“Been here before?” Lin Chong asked.

“Never.” Lu Junyi’s voice had a hush to it, as if they were in a temple.

Lin Chong led the way up the empty boulevards, toward the massive central structure that was White Tiger Hall.

Why had Gao Qiu called her friend here?

Perhaps it was nothing more than convenience. Still, her stomach remained unsettled, a quivering in her gut.

She reminded herself, again, that she’d not personally witnessed Gao Qiu’s rumored conduct with women. Not strictly speaking. Perhaps, once or twice, a girl fleeing in tears with disarrayed clothes; conclusions could be drawn, if one chose to draw them. Or a whisper from the odd visitor, to have a care, veiled words and knowing looks. Or sometimes a sense of how Gao Qiu acted in person—nothing to pin down, but a way he balanced his lean body, looming over people, asserting ownership over young women in his vicinity in a manner that always crawled under Lin Chong’s skin.

Never enough for her to speak, of course. Never enough to say that he was wrong, that she was challenging him, even if it would have been possible for her to do so. He was her superior; he was a Grand Marshal and personal friend to the Emperor; attentions from someone like him might be considered as much flattery as threat.

And were, often.

The young women would have to learn to look after themselves, Lin Chong always thought. As she had, when she was young enough to attract such notice.

The steps of White Tiger Hall were as long and polished as the elegant grandeur of the building. As at the district gates, guards stood at either side of the entrance, spears upright in hand, the small rectangular scales of their layered armor gleaming dark in the sun. Their postures had an exacting straightness that Lin Chong noted with approval. She stopped halfway up the steps to untie her sword.

“Do you carry any weapons?” she asked Lu Junyi.

“No. Why?”

“None are allowed in White Tiger Hall, on pain of death. It is considered a potential assassination attempt against the Emperor.”

Lu Junyi stared, her jaw gone a little slack. “I shudder to think if I did not have you accompanying me.”

“The guards would have asked, if you did not know to disarm yourself,” Lin Chong assured her. That was not what worried her.

She surrendered her sword to one of the guards—a man who had trained with her, as all the newer guards had. He and the others saluted her, and Lin Chong and Lu Junyi passed into the hall.

The inside of the hall spread wide and deep and luxurious, high-ceilinged and ornate. Carved wooden screens gave way to gilded and painted rails around the perimeter, and the most detailed of woodwork made monkeys and cranes, phoenixes and dragons, tortoises and qilin, all dancing in studied elegance up the walls and beams.

A long wooden table stretched the length of the hall, one Lin Chong could only imagine regularly seated the most powerful men in the Empire, with the Emperor at their head.

Right now, instead, at the head of the long table slouched Gao Qiu. Eating.

He lounged alone, his robes open down the front and fallen off his shoulders to pool at his elbows, baring his sinewy chest. Gao Qiu was a thin man, an athlete and footballer, with a thin mustache and beard in a thin beaky face that somehow matched his physique. In front of him, spread on silver platters of varying size, was a spread that would have sated five men: savory, delicately sliced duck, crab-stuffed oranges, bird’s nest soup, scallops swimming in sauce, braised mutton and pork belly, a whole chicken on a bed of lotus leaves… aromatic plates of steamed vegetables, bowls of dried fruits, and raw fish in such fine thin sheets it was almost transparent. Gao Qiu picked among them with a set of silver chopsticks joined at the top with a fine silver chain.

The scene was so disconcerting Lin Chong wondered if she had invented it. Or had she invented her reverence for this hall, for the central district itself? If a man was best friends with the Emperor, did he simply avail himself of the right to feast wherever he pleased, because to him these things were nothing?

Lin Chong could not grasp having such a position. Such a view on the world.

Lu Junyi stepped just past the foot of the table and bowed. “Honorable Grand Marshal. I hope you do not mind that I have brought my friend, Honorable Master Arms Instructor Lin Chong. She has been invaluable in discussing these calculations with me, and I would lean on her counsel for our discussion.”

If Gao Qiu was bothered by the request he gave no sign. “Of course, of course,” he said, waving them in, and then called for a servant. “Boy! Table settings for our guests!”

The two women crossed the hall carefully. Lu Junyi led the way to place herself with cautious respect at Gao Qiu’s right hand, at the long, empty wooden table. Lin Chong settled next to her.

“Will you have some wine?” asked Gao Qiu, sucking scallops off his chopsticks. “The finest yellow rice wine, aged to perfection—I’ll wager you have never tasted its like.”

Lu Junyi and Lin Chong both tried to demur. “I do not have the constitution—” started Lu Junyi, at the same time Lin Chong attempted to say, “You do me too great a compliment—”

Gao Qiu swatted down their protestations with a hand. “Boy! Two cups of wine for the women. Wine will be necessary. You’re here to discuss such a boring lot.”

“Marshal Gao,” Lu Junyi began. “The availability of the modern printing press gives us such a fine opportunity. I believe it could be a great boon to the Empire if licensed presses could begin issuing official paper banknotes, guaranteed by the Imperial Throne. Merchants would thrive if not weighed down by coin or metals, and large purchases could happen with the most frictionless ease. If we printed an expiration date of three years, the economic—”

“Not yet, not yet,” Gao Qiu cut her off. “Not until we’ve dined and supped. Here, partake of this duck, it is the tenderest in the region!” He stabbed at the dish with his chopsticks. Servants were placing matching silver plates and cups before Lin Chong and Lu Junyi, along with wine and fragrant white rice.

“You are most kind,” Lu Junyi murmured. “I fear we intrude upon your hospitality too much.”

“Nonsense,” Gao Qiu said. “Now eat, and drink, and let us talk of something less stultifying than money. How gauche and tired a topic.”

Lin Chong could not help running her eyes across the silver tableware and rich, exquisitely prepared food. When Lin Chong had been a very small child, her family had been lucky to have meat some days, instead of only rice and cabbage—or occasionally nothing but the last handful of grains boiled thin in water. It was a long ago memory, but the hungry ache of it was real.

Only those who had money could dismiss its concerns as gauche.

Lu Junyi made polite conversation with the marshal while Lin Chong nibbled at some slices of the duck. Its promised tenderness melted on her tongue, but she could not taste it. She did not share in the wine—except when Gao Qiu urged it and would accept no other answer; then Lin Chong only touched her lips to the liquid, nothing more.

“We ladies have such weaker constitutions,” Lu Junyi put him off, laughing, when Gao Qiu tried to protest their temperance. “I am confident you could drink barrels full, Marshal Gao! But you must forgive our more fragile state, especially so early in the day.”

Lu Junyi might desire a greater social latitude for women, but she was not afraid to use her femininity to advantage, Lin Chong noted.

“My master arms instructor has no weak constitution, eh?” Gao Qiu slapped a hand upon his thigh. “Master Instructor Lin! You have the constitution of a man, surely.”

“Forgive me, Marshal. I must retain my wits for my duties today,” Lin Chong said.

“So serious, this one,” Gao Qiu said to Lu Junyi, conspiratorially. “She puts my other officers to shame. Never any fun. Never a bit naughty.”

Lin Chong knew too well what would happen if she ever zigzagged off an arrow-straight path. She had no margin for raucous missteps, not the way her male colleagues did.

Lin Chong did not resent the fact. But it was still a fact.

“I strive to serve you well,” Lin Chong said to Gao Qiu. “And to serve His Imperial Majesty the Emperor.”

Gao Qiu guffawed at her solemn answer, but allowed the conversation to turn.

Lu Junyi managed to engage him in small talk until he permitted, with great, put-upon groaning, for a modest discussion of economics. By that time, Lin Chong’s hips were beginning to ache from sitting for so long. How long would this stifling meeting go on? Her usual duties were far more active. Most days, at this time she’d be wrapping up her own private exercise time and returning to her quarters to prepare for leading the morning drills.

She had been too hasty in her apprehension about this meeting. Clearly Gao Qiu only wanted to bask in his status; that was why he had called for the appointment in this room. Lin Chong began to feel exceedingly foolish.

Next time she would not let such flights of fancy take hold.

Gao Qiu finished hearing Lu Junyi’s proposal—at least, as much as he was willing to hear. Though Lu Junyi gave little sign of it, Lin Chong had known her old friend for enough years to note the slight stiffness of annoyance as Gao Qiu effusively dismissed her.

“I thank you for this audience, Marshal,” Lu Junyi said. She stood and bowed very properly. “I await your wise decision on the matter.”

“I’ll take it to my advisors,” Gao Qiu said, with a casualness that suggested anything but. “And to the Emperor, it will ultimately be his decision. I daresay he would feel more positively toward such a daring proposal if he heard it from so graceful a woman!”

He laughed. Lu Junyi and Lin Chong smiled politely.

“I would be glad to come repeat it for His Imperial Majesty,” Lu Junyi said.

Gao Qiu laughed harder, as if she had told a joke. “That would be something to see! Now go, go. I can’t say this was interesting, but you have an engaging manner, at least. Wait, Master Arms Instructor—I would speak with you a moment longer.”

Lin Chong had risen to leave with Lu Junyi. At Gao Qiu’s words, she paused and nodded to her friend. “I shall see you later, Lady Lu.”

“Good day, Master Instructor Lin,” Lu Junyi replied, equally formally, and retreated out of the hall.

“Sit with me,” Gao Qiu said, patting the space Lu Junyi had left. “I desire a report on the state of my men. How do they fare?”

Considering that Lin Chong reported this to Gao Qiu weekly in the more mundane setting of his yamen, this extra request was puzzling. Sensing Gao Qiu did not wish her usual level of detail, Lin Chong answered in summary. “I have no complaints about the improvement of their technique, but I continue to be concerned with their discipline. Their carelessness with the military hierarchy troubles me.”

“Yes, yes, so you’ve told me,” Gao Qiu said. “Better for them to be a bit undisciplined, no? Then they can’t rebel against the state!”

He laughed like it was another joke, but Lin Chong wondered if it was. She’d grown frustrated to the point of stating her concerns baldly, and still neither Gao Qiu nor the Emperor would take such matters seriously. Lin Chong could not be the only person who had heard the whispers of border skirmishes to the north—an undisciplined army would break against determined invaders like a wave upon stone.

If the Emperor thought he could prevent a coup against his throne by weakening his own men, Lin Chong feared the whole Empire would pay a price for it in blood.

Lin Chong herself was not technically a soldier—arms instructors were purely civilian positions, scholar-officials with a specialized skill set, bureaucrats who happened to handle weapons. But even in this time of relative peace she’d been adjunct to a number of minor conflicts as part of her duties, and the battlefield rarely respected a lack of official military designation once weapons had begun to fly. Even beyond her experience, she had taught, broken bread with, or drunk wine and spirits with enough officers over the years to fear her own knowledge of army readiness might exceed the marshal’s.

Or at least, exceed this marshal’s. Gao Qiu’s high military rank notwithstanding, Lin Chong had private doubts about how many times he’d ridden with his troops.

Such a thing was never to be voiced, of course. Nor was it for her to make any broader change regarding the Guard’s discipline. She could only enforce it within her own drills, as she trained the men in sword and truncheon, battle axe and spear, lance and crossbow and rake and every other weapon they might be called upon to handle.

Gao Qiu held a chicken leg with two fingers, slurping the soft flesh off the bone. “The men say you are a most extraordinary instructor, you know.”

Lin Chong blinked. Her ruminations on tactics and military preparation fled.

She did not know how to respond. It was a shocking thing for Gao Qiu to have been told by any in the Guard, and even more shocking for him to relay it to her. The men respected her, she knew—she had no doubt of that. She ensured it. But no praise had ever been rained upon her for correctly doing her job, nor should it have been. Her reward for excellent conduct was that she was granted the chance to continue doing her job.

Gao Qiu’s praise made every small hair on her neck and back prickle.

He was singling her out. Lin Chong strove with every moment of every day to avoid being singled out.

“The men speak too plainly,” she settled on after a beat. “I serve at the pleasure of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor.”

“Don’t we all.”

Gao Qiu’s words were slurred slightly, sotted with wine. He tossed the chicken bone to his plate and leaned forward, letting his hand fall across Lin Chong’s wrist.

Lin Chong froze.

In the first instant she wanted to believe it was an accident. Or that she imagined it. The contact jolted her with its wrongness, the violation of every social boundary.

Her mind kicked—it’s only a drunken mistake, he means nothing by it, nothing—even as every instinct inside her screamed.

Even as she knew.

The thought welled up: But I am too old—I was past this—

How could she respond without causing any slight? Without embarrassing the marshal, or provoking his ire?

None of the occasional complicated navigations of her youth had entailed rejecting a Grand Marshal and bosom friend of the Emperor…

The unreality of the central district, of White Tiger Hall, rang eerily through her, so far from anything known or familiar.

Carefully, she went to move her hand away, as if to reach for her wine. Casually. As if no other hand pressed hers and made her throat close like she wanted to be ill. Marshal Gao would let it drop. She would give him the space for a dignified fiction, a polite deniability; this never happened.

Instead, the moment she moved, his hand lashed over like the strike of a viper. His fingers tightened around her wrist, the force so savage it was as if his bones clamped against hers.

Lin Chong could have broken away, but at the same time she could not move.

“Why so hasty, my master arms instructor?” Gao Qiu asked.

“Your pardon, Marshal.” Lin Chong’s voice did not feel like her own, tinny and strange. “Please excuse me. I must go to lead the morning’s drills.”

“They can wait. Come, sit closer to me.”

Lin Chong did not obey. Her limbs were leaden.

She could not understand what was happening, or why, why now. Had she foiled some base intentions against Lu Junyi only to bring them upon herself? Had this been in Gao Qiu’s mind all along? But he would not have expected her here today, how could he have expected her… why were they in White Tiger Hall…

The question kept circling, echoing in her ears, as if it were of any importance at all.

Gao Qiu tightened his grip, forcing Lin Chong toward him. She resisted without moving, her arm a tug-of-war between them for a long and terrible moment of space. She didn’t know what else to do.

“Come here,” Gao Qiu barked, and reached his other hand as if to yank at the front of her coat.

Lin Chong’s reflexes reacted for her before she could decide. She wrenched away, breaking his hold against her wrist, and scrambled up from her seat.

“How dare you.” Gao Qiu lurched to his feet, his skin reddening across his chest and face. “You are in my employ! You will do as I say.”

“Marshal, I beg you—” Lin Chong was backing up. The trap was on all sides. She could not run. She could not fight him. Her shoulders hit the lacquered wall. “You do me too great an honor. I am old and tough. You deserve a woman younger, more beautiful—”

“I deserve whatever I want.” He heaved into her space, hands against the wood on either side of her, his breath hot on her skin and stinking of wine. “You work for me.”

Lin Chong flashed back almost brutally to merely earlier that morning, when she had told her students: The control you have over yourself will equip you, unmatched, in any situation you encounter. The lie twisted hard in her chest, like the blade of a knife.

If she fought Gao Qiu, she would win. The imaginary future splayed before her. She would win. She could bloody him here, in White Tiger Hall—if she wished, she could kill him. She would win while burning her position, her own life, her future; flames that consumed every path or chance or ending for her… The consequences would spiral, each collapsing into the next until they poured into an avalanche. Not only her place torn away from her, but then the Emperor, His Imperial Majesty, the Lord of Heaven, the embodiment of the Empire, who was boyhood friends with Gao Qiu—

The imagined future in Lin Chong’s mind swirled into a maelstrom, choking her. It could not be thought of.

Gao Qiu fisted a clumsy hand against the front of her coat. The hand crawled over, groping to shove against the bottom of her breast through the layers of cloth.

She felt dizzy.

Her inhales moved her chest against his grip, and sick crawled up her throat. She tried to stop breathing, stuttering to shallowness, to the stillness of a corpse.

“Better,” Gao Qiu huffed against her face. “You’ll see. I can be a benevolent man.”

Lin Chong’s mind had vibrated apart from her body. She could withstand this. She had withstood worse. It would not last very long. Less than one watch of the morning, surely. Half that, or a quarter. That was no time at all. No time at all.

And then she would be free to leave. She told herself she was transported to that time already, only moments hence. Walking freely from the hall, returning to the southern district and resuming her duties, unencumbered on the streets. Away from here.

It would not be long at all.

Gao Qiu’s hand squeezed rough against her, disarraying her coat and bruising her flesh beneath. The pain was there, but small. She could bear pain.

His breath snarled warm and lustful against her ear, and he took her by the shoulder to shove and turn her, the wall crushing against her chest. The scents of cedar and dried lacquer filled her nostrils. Gao Qiu pawed inexpertly at the back of her coat, her robes, shoving the cloth up and aside.

It would be over quickly. She could withstand… not long at all…

His hand came up and grabbed her wrist from behind, slamming it to the wood, pinning her arm.

Thought and feeling surged back into Lin Chong’s body like two ships colliding at full sail. Instinct rebelled and reacted before her sense could override it.

She twisted, sharp and hard, breaking his hold while her arm followed to sweep his grasping hands aside. He squawked angrily and lunged to pin her body. Her foot came out, upsetting his balance, his face falling straight into the hard strike of her palm.

Gao Qiu staggered back, his hands coming up and muffling him as he yelled, “Whore!”

It was only then that Lin Chong’s mind caught up with what she had done.

The hall closed in on her, suffocating. This was worse—so much worse—she should have—she should have shut her eyes, she should have let him, the discomfort would have lasted only moments, what had she been thinking?

Warring impulses battled within her, paralyzing her. Should she run? To where? Could she salvage this? Soothe his ego? Perhaps once he was sober—

“Strumpet! Whore! You belong to the Emperor. You belong to me!” Crimson had begun to dribble below Gao Qiu’s nose, pooling against his upper lip. He railed through it, bloody spittle flecking across the space between them to pebble against Lin Chong’s face. “I gave you this position. I gave it to you! People warned me about you, they said it was only trouble, hiring a woman, but I made you!”

His history was so wrong she could not even have found the words to argue it—she had been working up as an arms instructor before he was ever a Grand Marshal; he had never taken more than cursory notice of her career or her as a human being under his command—he took her reports and stared past her, through her, until today, until today…

“I made you, and I can unmake you. Guards!” Gao Qiu roared.

It was the last moment Lin Chong could have fled. Even in that moment, she did not believe, could not believe; she had envisioned the reality but could somehow not conceive that it would come to pass.

Two of the guards sprinted in from the entrance, the dark layered plates of their armor rattling, their spears lowered and searching for the danger. Imperial Guards responding to a threat were the one, the only exception to the ancient prohibition against weaponry here, a permissible violation of the deep taboos when some terrible boundary had already been crossed.

The guards stopped a short distance from Lin Chong and Gao Qiu, looking between their two superiors in confusion.

“Where is the master arms instructor’s sword?” Gao Qiu barked at them.

“I have it, Marshal,” one of the guards answered, gesturing to his side, where Lin Chong’s sword hung next to his own.

“Give it to her!” ordered Gao Qiu.

The guard hesitated, mired in confusion, and Lin Chong had the howling, incongruous thought that the lack of instant discipline she had so complained of was giving her one moment more of reprieve.

“This is White Tiger Hall,” the guard said doubtfully, with a timid look to Lin Chong.

She knew him. A man called Shu. Decent in drills, good-natured, though little intelligence that he did not borrow from others.

“I said give it to her!” Gao Qiu screamed.

The guard could not disobey the Grand Marshal. He hastily twisted to remove the sword and stepped forward to offer it to Lin Chong.

She did not reach to take it. Of course she didn’t. She was still a master arms instructor of the Imperial Guard, and she knew the laws here—especially the marrow-deep ones, the ones etched into the bones of anyone who lived and worked in these districts of the Imperial City. This was White Tiger Hall, and Gao Qiu expected her to… to do what? Become traitor? Turn into a criminal on his behalf, so he could feel justified in whatever he did next?

She would not do it. He had every advantage, but she would not give him the excuse.

Gao Qiu lumbered forward, took Lin Chong’s scabbarded two-edged sword, and flung it at her chest. Lin Chong jerked back, forcing herself to raise her hands and avoid catching it. The sword clattered to the floor against her feet.

Lin Chong winced with the incongruous reflex of someone who did not treat her weapons that way.

“You see Master Arms Instructor Lin Chong,” Gao Qiu proclaimed to the guards. “She possesses a weapon in White Tiger Hall—you see it with your own eyes. I order her arrested for attempted assassination against the Emperor!”

Lin Chong’s only thought, dulled as if it occurred to her from a great distance away, was that she should have known. She should have seen ahead.

It did not matter whether she had caught the sword or not. It did not matter that she provided no excuse. It did not matter that everything she had done, her whole life, was intended to live within the strictness and narrowness of the most upright member of society, to serve the Empire without straying.

Numbness overtook her. The guards hesitated again—especially approaching their master arms instructor, especially after the farce they had witnessed and everything they knew to be true. But they could not disobey the Grand Marshal.

Lin Chong would not have expected them to.

Hands clasped over her arms, dragging her wrists behind her, and the guards marched her out of White Tiger Hall. The last she saw of Gao Qiu, he lounged against the polished table, blood dribbling down onto his bare chest, his eyes pinned on her with all the knowledge that he had won.

Excerpted from The Water Outlaws, copyright © 2023 by S.L. Huang.